It is almost ten years since the Arthur Wishart (Franchise Disclosure) Act was introduced in Ontario. The Act seeks to protect often unsophisticated purchasers of franchise rights by requiring that certain disclosures be made to franchisees prior to entering into a franchise agreement. If these disclosures are later discovered to have been deficient,the Act also provides the franchisee with the right to rescind the franchise agreement. Section 6(6) of the Act outlines the specific financial remedies that are available to the franchisee in the event of rescission.

There have been few reported decisions dealing with issues of quantification under this section of the Act; moreover, based on our experience, these remedies are often a source of confusion for both plaintiffs’ and defendants’ counsel. In the following paragraphs, we set out a framework for conceptualizing these remedies.

In brief, the Act requires that, upon rescission, the franchisor:

a. Refund the money paid by the franchisee to the franchisor; b. Purchase the franchisee’s remaining inventory at its original cost; c. Purchase the franchisee’s supplies and equipment at their original cost; and d. Compensate the franchisee for all losses incurred in acquiring, setting up and operating the franchise not included in clauses (a) through (c).

Though not explicitly stated, the underlying goal of this section of the Act appears to be to restore the franchisee to its financial position at the date of acquisition; this understanding of the legislation was made explicit by Justice Murray in his ruling in Payne Environmental Inc. v. Lord and Partners Ltd. [2006] O.J. No. 273, one of the few reported cases dealing explicitly with the issue of quantification. This is accomplished by two main steps.

Under clause (d) the Act requires the franchisor to compensate the franchisee for any losses incurred in operating the franchise. Once this step is completed, the owner’s equity section of the balance sheet will have been restored to its original level. However, the Act also recognizes that upon rescission, assets such as leasehold improvements, specialized equipment and inventory, and certainly the franchise rights, are of minimal value to an individual who no longer wishes to engage in the business of the franchise, and that these will also be difficult to sell to a third party. Clauses (a) through (c)therefore allow the franchisee to sell these assets to the franchisor at their original cost.

The end result of these remedies is to return the franchisee to his or her financial position immediately prior to entering into the franchise agreement. This can be illustrated through a simple example.

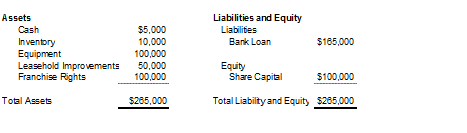

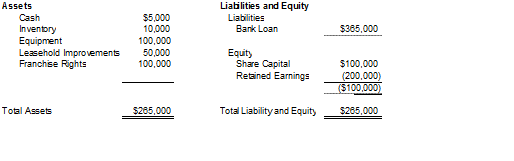

Suppose Mr. Jones purchases a franchise for an initial franchise fee of $100,000; there are no ongoing royalty payments. In order to set up the franchise, Mr. Jones purchases $100,000 of equipment and $10,000 of inventory; he also spends $50,000 to renovate his leased premises. Finally, the business also requires a cash balance of $5,000 on hand to fund operations. These assets, which total $265,000, are purchased with $100,000 of Mr. Jones’s own money (i.e. equity) and $165,000 of bank financing. At the beginning of operations, the balance sheet looks as follows:

In its first year of operations the franchise is unsuccessful and suffers operating losses of $200,000; to finance these losses, Mr. Jones takes out an additional bank loan of $200,000. At the end of the year, the owner’s equity section of the balance sheet has decreased from positive $100,000 to negative $100,000:

Upon examining his franchise disclosure document at the end of the year, Mr. Jones realizes that certain required information is absent. He files a Notice of Rescission.

Upon examining his franchise disclosure document at the end of the year, Mr. Jones realizes that certain required information is absent. He files a Notice of Rescission.

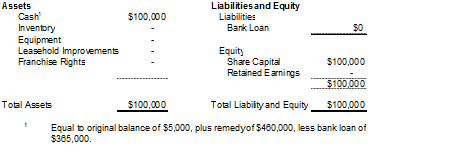

Under subsection 6(6) of the Act, Mr. Jones is entitled to $460,000, as follows:

(a) Franchise Rights – $100,000; (b) Repurchase of Inventory – $10,000; (c) Repurchase of Equipment – $100,000; (d) Reimbursement for Startup Costs (=Leasehold Improvements) and Operating Losses – $50,000 + $200,000.

Mr. Jones uses the $460,000 to pay off his bank loan of $365,000, leaving him with $95,000 in excess cash; all of his assets, with the exception of the $5,000 in cash on hand, are sold to the franchisor. His balance sheet now shows owner’s equity of $100,000, as follows:

The $100,000 in cash, unencumbered by any liabilities, is precisely the amount of money put into the franchise by Mr. Jones. He pays himself a tax-free dividend of $100,000 and walks away from the franchise as though it never existed.

Common Errors In our experience, rescission claims under the Act often belie a lack of understanding of the interaction between the four clauses of section 6(6), resulting in a duplication of various items; we hope to explore some of these common errors in a future article. Once the fundamental principles underlying the wording and mechanics of the Act are understood, proper quantification of the remedy becomes more manageable.

The statements or comments contained within this article are based on the author’s own knowledge and experience and do not necessarily represent those of the firm, other partners, our clients, or other business partners.

By: Ephraim Stulberg. Published in The Lawyers Weekly, May 13, 2011.