For quite some time now, much has been said about the world’s move toward clean energy and the goal toward net zero by 2050. To achieve this, demand will continue to grow for certain critical minerals, such as lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, etc. But how can this demand be met with ethically sourced minerals? While some think that deep-sea mining is a viable solution, others oppose this practice, citing environmental concerns.

Deep-sea mining consists of the extraction of mineral deposits from the seabed, such as copper, cobalt, nickel, zinc, silver, gold, and rare earth elements. In simplistic terms, extraction of these minerals could likely involve the removal of the nodules, deposits or sea-bed layers from depths of up to 6,000 meters.

There are three general types of mineral resources on the sea floor:

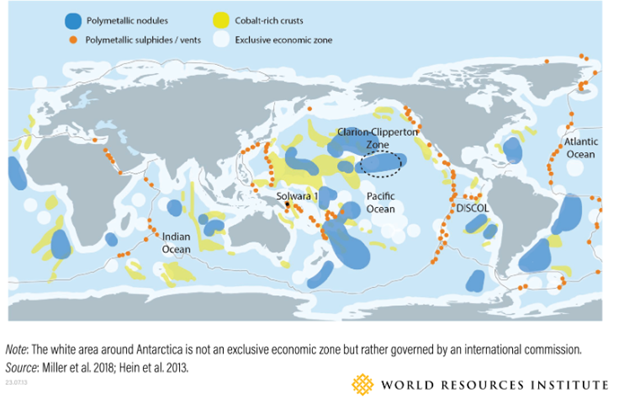

- Polymetallic nodules – These contain manganese, nickel, copper, and cobalt and have been found in abundance in a few ocean basins. One of the largest deposits sits on the ocean floor of the eastern Pacific Ocean, in an area denominated the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

- Polymetallic sulfides – Consisting of sulfide-rich deposits, these are typically found in underwater areas with volcanic activity, near tectonic plate boundaries.

- Cobalt crusts – Cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts can be found on the sides and summits of underwater mountains, many of which are located in the western Pacific.

The map below shows where the above resources are generally located:

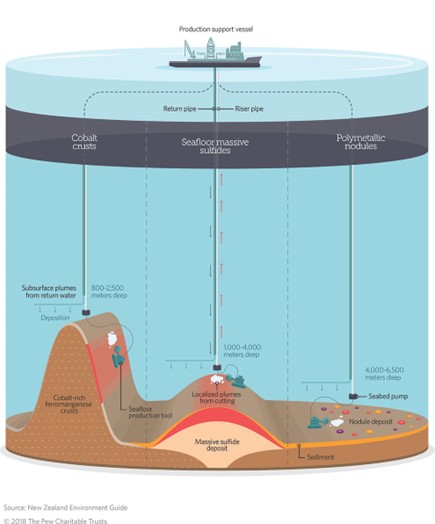

The exploitation of the different minerals depends on where they are located. That is, mining polymetallic nodules would likely involve separating the modules off the muddy sea floor, polymetallic sulfides would involve removal of the sulfide-rich deposits resulting near hydrothermal vents, and cobalt crusts would likely involve removal of a layer of seabed surface where the cobalt minerals can be found. In all cases, the extracted materials would be sent to the surface, where they would be separated, later returning water and sediments back into the ocean.

The exploitation of the different minerals depends on where they are located. That is, mining polymetallic nodules would likely involve separating the modules off the muddy sea floor, polymetallic sulfides would involve removal of the sulfide-rich deposits resulting near hydrothermal vents, and cobalt crusts would likely involve removal of a layer of seabed surface where the cobalt minerals can be found. In all cases, the extracted materials would be sent to the surface, where they would be separated, later returning water and sediments back into the ocean.

While some exploratory mining has occurred to date, on a small-scale test basis, deep-sea mining is not performed commercially. Currently, the UN’s International Seabed Authority (ISA) is tasked with the regulation of deep-sea mining. Some nations are already applying to the ISA for permits in relation to deep-sea exploration or mining. However, citing environmental concerns, a growing number of countries have opposed the practice, calling for a moratorium, delay or even ban. While countries may still mine within their own domestically controlled waters, known as exclusive economic zones (or EEZs), they must obtain permission from the ISA to mine outside of these zones.

Since 2014, ISA has been in the process of developing regulations, or a mining code, for the exploitation of mineral resources in the Area (the seabed beyond the national jurisdiction of individual countries).

In 2021, the Pacific Island nation of Nauru, after requesting permits to mine, invoked a provision in the UN’s Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), known as the “two-year rule”. It obligated the ISA to consider and provisionally approve mining within a two-year period. However, at the two-year mark, in 2023, consensus on regulations was not reached. ISA is now working to adopt regulations by 2025.

In the meantime, ISA has granted 30 mining exploration contracts covering 1.4 million square kilometres of the seafloor; of these, 17 correspond to sites in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

Despite the push, many countries, such as Canada, New Zealand, Switzerland, Mexico, the United Kingdom, and the Moratorium Alliance (Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Palau, and Samoa), call for a moratorium. Those that call for a precautionary pause are Brazil, Costa Rica, Chile, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Kingdom of Denmark, Monaco, Panama, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Vanuatu. France is the only country that advocates for a ban altogether.

Proponents of deep-sea mining argue that this practice could help meet the world’s increasing need for critical minerals in the global effort to attain net zero as the world increases its reliance on zero-carbon technologies such as wind and solar power, electric vehicles, and battery storage. However, concerns with the potential environmental impact associated with deep-sea mining drive some of the opposing states/countries to advocate for more scientific studies to be conducted first, before adopting a mining code

Some risks involved with deep-sea mining include direct/indirect harm to marine life, which may lead to biodiversity loss; some organisms may be harmed by mining vehicles/equipment or by the warm mining wastewater (return water) through overheating and poisoning. Additionally, deep-sea mining may cause long-term disruption to deep-sea species and their ecosystems by creating an environment with loud noises and mild pollution, affecting their feeding and reproduction; these environments would typically be dark and silent environments. Also, the wastewater discharged from mining vessels could be a potential threat to open ocean fish and invertebrates, which could negatively impact international fisheries. Another concern/risk associated with deep-sea mining involves the potential habitat loss of coastal communities due to the building of shoreline facilities that would be needed to process the minerals mined.

Thus, the regulations that the ISA eventually develops must address these potential threats. But the ISA itself is not devoid of controversy. Its past secretary general, Michael Lodge, faced criticism by some ISA member countries over perceived biases resulting from his close relationship to executives of seabed mining companies. However, just this past August, members of the ISA elected Leticia Carvahlo of Brazil as the new secretary general. Carvahlo promised to bring accountability to the governance of the ISA itself, operating under political transparency. As a marine biologist, she is the first oceanographer to oversee the ISA. Her appointment comes at a pivotal time, and it will be interesting to see how the future of deep-sea mining unfolds.

But how does this impact the insurance industry?

Although deep-sea mining is young and its rules and regulations are still being developed, due to the risks involved, now four major global insurers (Swiss Re, Hannover Re, Zurich Insurance Group and Vienna Insurance Group (VIG) have decided to exclude deep-sea mining from their underwriting portfolios. Thus, the licensees or mining companies themselves would have to bear the risk and burden involved in this activity. In the future, as more is understood about this type of exploitation and many of the concerns ameliorated, it may be possible that insurers’ interest in underwriting these risks may shift.

The deep-sea mining industry is facing much uncertainty, from its legislation to potential environmental and economic risks involved to the early-adoption risks associated with new industries. Insurers face a challenging decision on whether to insure deep-sea mining activities for both exploration (as is currently being done) and exploitation when the time comes.

The statements or comments contained within this article are based on the author’s own knowledge and experience and do not necessarily represent those of the firm, other partners, our clients, or other business partners.

https://www.wri.org/insights/critical-minerals-us-climate-goals

What We Know About Deep-sea Mining and What We Don’t | World Resources Institute (wri.org)

https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2017/02/deep-sea-mining-the-basics

Deep-Sea Mining Could Begin Soon, Regulated or Not | Scientific American

Deep-sea mining: ISA’s Carvalho plans to resolve its murky future (cnbc.com)

Seabed mining leader vows to investigate predecessor – E&E News by POLITICO (eenews.net)

Switching Directions, ISA Picks an Oceanographer for its Top Post (maritime-executive.com)