It is becoming increasingly important for attorneys to understand financial statements and their relevance to various types of business and legal situations. The non-accountant attorney will greatly benefit from a basic understanding of the key principles of accounting. Equally important is the understanding of forensic accounting and how the forensic accountant can be an asset to the attorney.

What is Accounting?

Accounting is the backbone of business. It is the discipline of measuring, communicating and interpreting financial activity. The end result should produce a financial image of the business that supports the decisions of managers, informs investors of business developments and assists in keeping the business profitable. Accounting is also widely referred to as the “language of business” [1].

What do Accountants do?

A number of disciplines are involved in accounting. A few of the major accounting fields are:

Bookkeeping

At the root of all accounting is bookkeeping, the practice of recording transactions. Bookkeepers tend to focus on the details, recording transactions in an efficient and organized manner, and they may or may not see the overall picture.

Managerial accounting

These accountants typically work for a single company or entity and use the work done by bookkeepers to produce and analyze financial data for the business. An accountant can design reports that will capture all of the details necessary to satisfy the needs of the business – managerial, budgeting, financial reporting, projection, analysis, and tax reporting. These accountants may work among a large staff of accounting personnel and may be a controller or a financial officer of the company.

Public accounting

Many businesses, governmental organizations, non-profit organizations, and individuals use the services of a certified public accountant. (CPA). These accountants provide a wide range of services, including consulting on taxes, accounting, and auditing.

Auditing

An auditor can be either an internal or external auditor.

- An internal auditor typically works for a single entity and is responsible for checking the company’s records to ensure that they are correct and looking for problems such as inefficiency or criminal activities.

- External auditors are certified public accountants who are independent of the entity. An external auditor examines a company’s accounting books and records in order to determine accuracy and whether the company is following appropriate accounting procedures. An auditor issues an opinion in a report that states whether the financial statements present fairly the company’s financial position and its operational results in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

Forensic accounting

A forensic accountant applies auditing and accounting concepts and theories to investigate an actual or suspected situation involving actual or potential litigation – in other words, investigative accounting. Forensic accounting typically deals with activities like fraud, embezzlement, legal disputes, insurance claims, money laundering, or bankruptcies. Analyzing and investigating these situations requires an awareness of finance and accounting along with knowledge of the law and investigation skills.

Certifications Held by Accountants

Special designations or certifications that exist for accountants provide additional evidence of knowledge and competence beyond that provided by the college degree. These certifications allow accountants to project to clients the depth of their knowledge in a specialized field within accounting. The following are some of the various certifications available to accountants.

CPA – Certified Public Accountant

CPA is the statutory title of qualified accountants in the United States who have passed the Uniform Certified Public Accountant Examination and have met additional state education and experience requirements for certification as a CPA. In most U.S. states, only CPAs who are licensed are able to provide to the public attestation (including auditing) opinions on financial statements.

CFE – Certified Fraud Examiner

The ACFE (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners) established and administers the CFE designation. This designation denotes proven expertise in fraud prevention, detection, deterrence and investigation. To become a CFE, one must pass a rigorous examination administered by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), meet specific education and professional requirements, exemplify the highest moral and ethical standards and agree to abide by the CFE Code of Professional Ethics.

CVA – Certified Valuation Analyst

The CVA accreditation is a statement to the business, professional and legal community that an individual has attained a level of knowledge in business valuations that the National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA) considers exemplary and worthy of recognition by awarding the designation of CVA) To become certified by NACVA, the candidate is required to successfully complete a rigorous training and testing process. A pre-emptive requirement to becoming a CVA is that the applicant must be a Certified Public Accountant (CPA) registered in his or her state.

MAFF – Master Analyst in Financial Forensics

The MAFF credential is offered through a subsidiary of NACVA, the Financial Forensics Institute. It is designed to provide assurance to the legal and business communities — the primary users of financial forensics services — the designee possesses a level of experience and knowledge deemed acceptable by the Association to provide competent and professional financial forensic support services. Applicants can train in one of seven areas of speciality, any of which lead to earning one’s MAFF credential. Those areas are: Bankruptcy Insolvency and Restructuring, Economic Damages, Business and Intellectual Property Damages, Business Valuation in Litigation, Forensic Accounting, Fraud Risk Management, and Matrimonial Litigation. Earning the credential requires consideration of all of the person’s qualifications and commitment to the discipline; this includes prior education and experience, prerequisite and required training as provided (or recommended) by NACVA, testing, and post-requisite requirements for recertification.

ABV – Accredited in Business Valuation

Similar to the CVA, the ABV credential is administered by the AICPA and is conferred upon CPAs who have demonstrated the skill, education and experience necessary to satisfy stringent requirements. These requirements were designed to address certain areas of skill, education and experience that are critical to practicing business valuation successfully.

CFA – Chartered Financial Analyst

The CFA is a professional designation given by the CFA Institute that measures the competence and integrity of financial analysts. Candidates are required to pass three levels of exams covering areas such as accounting, economics, ethics, money management and security analysis. Before an accountant can become a CFA charter holder, they must have a minimum of three years of investment/financial experience and hold a bachelor’s degree.

CFF – Certified in Financial Forensics

A relatively new forensic credential was launched in the fall of 2008 by the AICPA. The credential combines specialized forensic accounting expertise with the core knowledge and skills that make CPAs among the most trusted business advisers. The CFF encompasses fundamental and specialized forensic accounting skills that CPA practitioners apply in a variety of service areas, including bankruptcy and insolvency, computer forensics, economic damages, family law, fraud investigations, financial statement misrepresentation and valuations.

Accounting Basics

You’ve probably heard the saying, “Money doesn’t grow on trees.” It means that money must come from somewhere—it doesn’t just appear. An accounting system is used to record the source and outflow of money from a business.

Double-entry bookkeeping

This is a method of accounting that lets you track just where your money comes from and where it goes. Using double-entry means that money is never gained or lost—it is always transferred from somewhere (a source account) to somewhere else (a destination account). This transfer is known as a transaction, and each transaction requires at least two accounts. An account is a record for keeping track of what you own, owe, spend or receive. For example, a phone bill is paid from a checking account and money transfers from your bank to the phone company. This is a transaction transferring money from a bank account to a phone expense account. This double-entry concept has been around since the 13th century, and its purpose has always been to reduce the likelihood of data-entry errors. In a double-entry transaction, an equal amount is always transferred from one account (or group of accounts) to another account (or group of accounts), keeping the books in balance.

Debits & Credits

Accountants use the terms debit and credit to describe whether an account is increased or decreased. Debits and credits are a system of notation developed before a concept of positive and negative numbers were in use. If a certain type of account normally has a debit balance, a credit balance is a way of denoting a negative quantity of that item. For example, your bank account is an asset and normally has a debit balance. If that account in your books has a credit balance, you owe the bank money (you’re overdrawn). Nobody inventing double-entry bookkeeping today would use left-and-right debits and credits–he or she would certainly use positive and negative numbers, which is exactly what almost all computer programs do that perform bookkeeping. It would be better to think of double-entry bookkeeping as a system (in the abstract sense of the word) in which the “entity” begins with nothing, and every change in assets (a debit to increase, a credit to decrease) has an equal and opposite reaction.

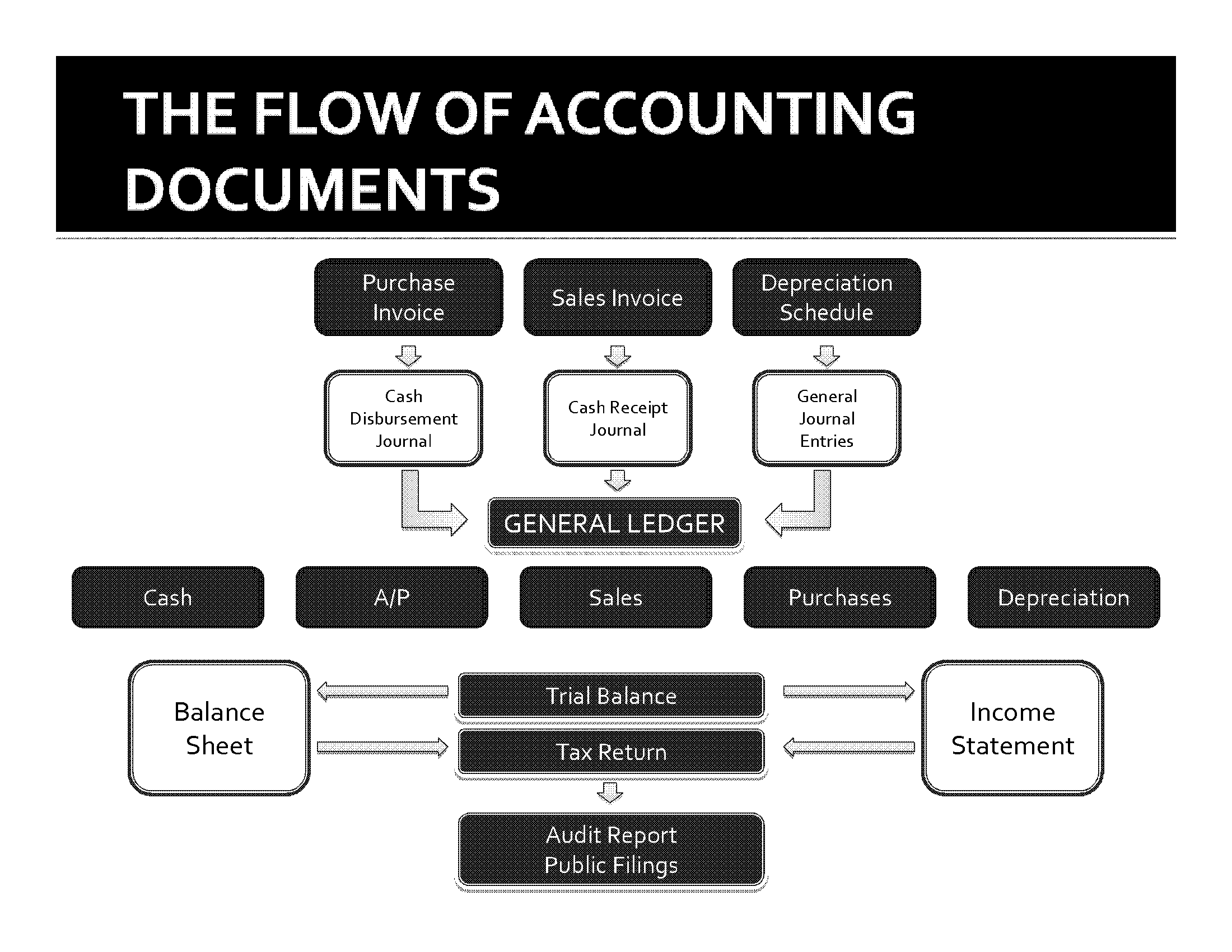

Source Documents

In the normal course of business, a document is produced each time a transaction occurs. Sales and purchases usually have invoices or receipts. Deposit slips are produced when deposits are made to a bank account. Checks are written to pay money out of the account. Bookkeeping involves recording the details of all of these source documents into multi-column journals. A simple diagram illustrating the flow of accounting documents is presented below and shows the progression from the source documents to journals to the general ledger accounts and to the resulting financial reports.

The Financial Statements

Financial statements are usually comprised of three separate statements: the Balance Sheet, the Income Statement (Profit and Loss Statement) and the Statement of Cash Flows. In addition to the basic financial statements, some financials will include Notes to the Financial Statements. Be sure to review this information for contingent liabilities and other important information.Financials statements can be compiled many different ways. The primary methodologies are cash basis, accrual basis and tax basis accounting.

- Cash basis accounting essentially reports revenues and expenses only when the cash is received or paid; whereas, accrual basis accounting reports revenues when they are earned and expenses when they are incurred.

- Accrual basis accounting attempts to match the revenues received with the expenses incurred and record them in the same accounting period regardless as to when the cash changes hands.

- Tax basis accounting reports revenues and expenses in accordance with the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). Tax basis financials should also identify if they are prepared on the cash or accrual basis of accounting.

Balance Sheet

The Balance Sheet has three sections: assets, liabilities, and equity. Assets less liabilities will equal equity if you have a proper Balance Sheet.

Assets

An asset is an economic resource that is owned or controlled by an entity; something of perceived value obtained through the exchange of another asset. For example, a law firm provides services to its clients creating an account receivable or cash. Assets are typically presented at cost (the price the company paid for them plus incidental costs). Some assets are presented at market value. Assets on a Balance Sheet are arranged in order of liquidity from greatest to least.

Questions to ponder:

- How liquid are the assets of the company?

- Is there sufficient cash to cover any litigation and settlement costs?

- How is inventory valued by this company?

- What are any “other assets” listed?

- How will this action or lawsuit impact the assets of the company?

- Are there any intangible assets? What are they worth?

- Does the company have a backlog of orders or work to help ensure profitability in the future?

Liabilities

Liabilities represent obligations to pay to lenders and creditors in the future for assets or services provided to the entity by the lenders or creditors in the past.

Questions to ponder:

- Are the debts shown real? Are loans from the owner ever going to be repaid?

- Are there any unrecorded debts (such as unpaid taxes, including payroll or credit card debt)?

- Are there any contingent liabilities (such as debt guarantees, environmental clean up costs, litigation, purchase commitments, etc.)?

- How are leases treated (capitalized or expensed)?

Equity

Equity is the book value of an ownership stake in a company. Equity is not typically representative of the true market value of a company. Rather, further analysis into the company’s assets, liabilities and future earnings capability is required to determine the true market value.Changes in equity typically occur from contributions or distributions of funds by the owners or a profit or loss by the company. Changes can also occur from the restatement of a prior period due to an accounting error.

Income Statement

The Income Statement details the revenue (also known as sales, gross income, or gross receipts) and expenses of an entity for the time period presented. Typically, an Income Statement presents a subtotal for the revenue and expenses from operations and then accounts for “other income and expenses” after the subtotal. These other income and expenses could be gain or loss on the disposal of equipment, incidental interest income from a savings account, etc. Almost every company’s Income Statement will be unique in one way or another, including how transactions are classified within accounts. A thorough understanding of how the company accounts for transactions is necessary. For example, some companies will include the collection of sales tax in gross revenue; others will not. The same goes for freight expenses passed on to the customer. Understanding the motivation for a company’s financial presentation will help you better understand their financials.

Revenue recognition

It is frequently a problem with revenue recognition issues when an accounting scandal comes to light. The increased pressure to meet earnings expectations of shareholders has driven management to manipulate the Income Statement. In privately held companies, the bonus or commission plans are usually the culprits behind manipulated earnings. For example, a sales agent whose primary compensation is based on commission and exceeding quarterly sales objectives will typically push hard towards the end of a quarter to push themselves into the next higher threshold of payouts. This can possibly be accomplished by changing the date of the sale closing or submitting sales that truly are not yet realized.Each reporting entity will have their own rules for revenue recognition. These rules are included in the IRC (Internal Revenue Code) or GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles), and are similar in some areas. They are complex and too numerous to discuss here.

Cost of goods sold

A company that maintains an inventory must account for the cost of goods sold and this can become a tricky situation. Cost of goods sold is generally calculated by adding the beginning inventory value to purchases during the period and deducting the ending inventory value. There is lots of room for interpretation in the inventory values. There are several accepted methodologies for calculating the inventory values, including: Last-In-First-Out (LIFO), First-In-First-Out (FIFO), and weighted average cost. In an economy of rising prices, a FIFO inventory will typically lead to a higher gross profit and a lower Inventory value on the Balance Sheet as compared to LIFO.

The most important thing to remember when reviewing Income Statements is to ask many questions about the company’s process for recording revenue and expenses, whether there are any related party transactions and what rules of accounting they are following.

Questions to ponder:

- Does the company pay personal expenses of the owner(s)?

- Are the owner(s)’ salaries/bonuses reasonable?

- Does the owner have an auto-mobile or entertainment allowance?

- Is the company’s revenue seasonal from month to month or from year to year? What causes the seasonality?

- Does the cost of goods sold percentage hold fairly steady? If not, why?

Statement of Cash Flows

The inclusion of a Statement of Cash Flows indicates the entity is on the accrual method of accounting. Because accrual accounting attempts to match revenue with expenses, the flow of cash will not typically match the Income Statement. The Statement of Cash Flows is a reconciliation of cash and cash equivalents. The Statement of Cash Flows is broken down into three sections: Operating, Investing and Financing activities. This statement provides additional information that cannot be gleaned from reading the Balance Sheet or Income Statement and is a good source of how the company uses its cash.

Reliability of a Financial Statement

Anyone can put together a financial statement. The quality of a financial statement will reflect the ability of the person who put the statement together. Certified Public Accountants (CPAs) have had formal training in financial statement preparation and have passed exhaustive testing on financial statement knowledge. Most states also have experience requirements for the preparation of financial statements under a more seasoned CPA. In addition, CPA licensure and compliance are regulated by state government bodies. Therefore, a financial statement prepared by a CPA would likely be more reliable than one prepared by a bookkeeper.If a CPA in public practice (as opposed to a Controller or CFO) issues a financial statement, certain reporting requirements reveal the level of assurance the CPA is providing regarding the financials. An “in-house” CPA is not required, or allowed, to issue one of these three reports for third party use.Keep an eye out for a “Going Concern” clause in the accountant’s report or the notes to the financial statements. A “Going Concern” clause indicates that the company is not financially stable and may not be in existence a year from the date of the financials.

Audited by a CPA

An Audit provides the highest level of assurance a CPA can offer for a financial statement. The CPA attaches an audit report to the financial statements with one of four general opinions: Unqualified, Qualified, Disclaimer, or Adverse. An unqualified opinion is the best level of assurance that the financial statements are presented fairly, in all material respects, in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). A qualified opinion means there are some material GAAP departures but they are not so severe as to result in a disclaimer or adverse opinion. A disclaimer of opinion essentially says that the auditor was unable to perform all the necessary procedures of an audit and therefore disclaims any opinion. An adverse opinion occurs when there is a very material departure from GAAP that cannot be reconciled. This type of opinion is rarely issued. An audit is designed to provide “reasonable assurance” that the statements are “free of material misstatement.”To perform an audit, the CPA examines on a “test basis” evidence supporting the amounts and disclosures in the financial statements and evaluates the accounting principles used and any significant estimates made by management.The CPA communicates with a sample of the company’s customers to verify that accounts receivables exist and are properly valued. The CPA observes the physical inventory count to verify that the assets exist and there is no obsolete inventory. Typically, the CPA communicates with all material financial institutions to verify the existence and value of the assets or liabilities and that no other liabilities exist with that institution.An audit does not provide a guarantee of accuracy of the information presented in the financials.

Reviewed by a CPA

A review is when a CPA formally examines a financial statement prepared by management. The accountant asks questions of management to make sure they are following GAAP or other pertinent rules. Also, the financial statements are checked mathematically and for internal consistency to see if the numbers “make sense.” If appropriate, the statements are compared to industry data (analytical review).The accountant is not required to check or test the balances in the accounts. An accountant can sit in a room with a company’s financial statement, the controller of a company and a sheet of industry data and perform a review without leaving the room or contacting any third parties.

Practice tip: Do not ask of a CPA witness “have you reviewed this financial statement?” Review is a term of art to a CPA. Unless they signed a review report they should answer no. They may respond: “I have examined the financial statement;” “I have analyzed the financial statement;” “I have observed many deficiencies in this financial report, but I have not reviewed it.”

Compiled by a CPA

This is where a client furnishes the financial information and requests that the accountant prepare proper financial statements. This can range from simply printing a computerized report (often from a program like QuickBooks) to recommending adjusting entries or taking a box of documents, the check book and credit card statements and creating a financial statement from that information.

Internal Financial Statements

The reliability of internal financials depends on the quality of the company and the quality of the accountant preparing them.

Tax Returns

Tax returns for business entities typically contain the information presented in financial statements in a slightly different format. Also, the amounts may be different because financial statements usually follow GAAP rules whereas tax returns usually follow Internal Revenue Code (IRC) rules.

When obtaining financial statements, determine the original reason for creation of the financials. Within the rules, there is usually room to “skew” the numbers to help present the best financials (for a bank loan) or the worst (for the tax return).

Financial Ratios

Ratios can help decipher a company’s financials and allow you to compare a company to an industry standard. Below are a few of many available ratios that are more useful in the litigation setting to determine if a company is financially stable enough to deal with a lawsuit.

Current Ratio

This ratio provides the user with an indication if the company will be able to pay its bills for the next year.The current Ratio is the number you get when you divide current assets by current liabilities. A one-to-one ratio shows the company will have just enough assets to pay debts.

Working Capital

Working Capital is the amount by which current assets exceed current liabilities. This is the amount of funds that are not committed to existing debts and can be used for new projects.

Acid Test

The acid test reveals how much cash the company can raise quickly. It is calculated by reducing Working Capital by the Inventory value.

Documents and Document Requests

Document requests are going to be specific for each case based upon the circumstances and desired goal. In accounting, the goal is to always be able to trace an amount on a financial statement back to a source document. Accountants love paper. We have listed many of the documents likely to be available in the accounting records of an entity, from the high level summary documents down to the detailed documents for each transaction.Most entities today use an electronic accounting system rather than maintaining a manual system. When requesting a large volume of documents that need to be analyzed, it is recommended that you obtain the information electronically. The electronic formats will vary greatly and your accounting expert may have the resources to open virtually every format, but don’t count on it – ask your expert what they can handle.

Be wary of accounting documents identified as “reports” or “transaction reports,” or the like. Obtain written clarification of what the report is purported to show because many of today’s accounting systems allow you to run numerous filters on reports so only certain transactions are included and shown. But often the report itself does not clearly detail the filters in place. Be sure to identify the time periods you wish to see and the frequency with which you desire to see the statements (i.e. monthly, quarterly, annually).

Documents that may be requested are listed below.

- Balance Sheets

- Income Statements

- Statement of Cash Flows

- Statement of Changes in Financial Position

- Budgets

- Job Cost Reports

- Federal Income Tax Returns

- State Income Tax Returns

- State Sales or Excise Tax Returns

These returns will provide revenue amounts. - Federal and State Payroll Tax Returns

These returns will provide detail of payroll amounts paid by the company and a listing of all the employees and amounts received. - Trial balance

The trial balances lists all of the general ledger account balances as of the date specified with total amounts being either a debit or a credit; used to prepare financials statements and tax returns. - Detailed General Ledger

The general ledger typically lists all the accounts with a beginning balance from the previous period, all the transactions during the specified period and the ending balance for each account. In more sophisticated accounting systems, certain transactions will be posted to the general ledger in batch entries, hiding the detailed transactions. This will result in a need to obtain the subsidiary ledgers. More basic accounting software such as QuickBooks and Peachtree do not have separate subsidiary ledgers. - Subsidiary Ledgers

The subsidiary ledger contains the detailed information for an account. Typically subsidiary ledgers are accounts receivable (A/R), accounts payable (A/P), sales ledger, payroll ledger, etc. - Journals

Accounting systems will typically maintain journals for each transaction. A common journal to be wary of is the General Journal, which is typically where general journal entries are made. General journal entries are an area to scrutinize because this journal bypasses the normal accounting process and enters a transaction directly to the general ledger and represent unusual or non-recurring transactions. Another journal is the sales and purchase journals. - Source Documents

These documents include a sales invoice, a bill or purchase invoice, a purchase order, requisition request, contracts, promissory notes, bank statements, brokerage statements, accounts receivable statements, inventory count sheets, cancelled checks, vehicle licensing documents, business licensing documents, cash register receipts, other cash receipts, articles of incorporation or other formation documents, by-laws, purchase commitments, marketing materials, leasing documents, etc.

Glossary [2]

Capitalized terms that appear within definitions of other terms are also defined in the glossary. Related terms are cross-referenced to provide a clearer understanding of their interdependent relationships.

Account – An accounting record in which the results of transactions are accumulated; shows increases, decreases, and a balance.

Accountant – Person skilled in the recording and reporting of financial transactions. (See CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANT.)

Accountants’ Report – Formal document that communicates an independent accountant’s: (1) expression of limited assurance on FINANCIAL STATEMENTS as a result of performing inquiry and analytic procedures (Review Report); (2) results of procedures performed (Agreed-Upon Procedures Report); (3) non-expression of opinion or any form of assurance on a presentation in the form of financial statements information that is the representation of management (Compilation Report); or (4) an opinion on an assertion made by management in accordance with the Statements on Standards for Attestation Engagements (Attestation Report). An accountants’ report does not result from the performance of an AUDIT. (See AUDITORS’ REPORT)

Accounting – Recording and reporting of financial transactions, including the origination of the transaction, its recognition, processing, and summarization in the FINANCIAL STATEMENTS.

Accrual-Basis Accounting – A system of accounting in which revenues and expenses are recorded as they are earned and incurred, not necessarily when cash is received or paid.

Adverse Opinion – Expression of an opinion in an AUDITORS’ REPORT which states that FINANCIAL STATEMENTS do not fairly present the financial position, results of operations and cash flows in conformity with GENERALLY ACCEPTED ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES (GAAP). The auditor will issue an adverse opinion when there is an existence of a material weakness on the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) – National professional membership organization that represents practicing CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS (CPAs). The AICPA establishes ethical and auditing standards as well as standards for other services performed by its members. Through committees, it develops guidance for specialized industries. It participates with the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) in establishing accounting principles.

Articles of Incorporation – (sometimes also referred to as the “Certificate of Incorporation” or the “Corporate Charter”) the primary rules governing the management of a corporation in the United States, and are filed with a state or other regulatory agency.

Asset – An economic resource that is expected to be of benefit in the future. Probable future economic benefits obtained as a result of past transactions or events. Anything of value to which the firm has a legal claim. Any owned tangible or intangible object having economic value useful to the owner.

Audit – The result of an independent accountant’s review of the statements and footnotes to ensure compliance with GENERALLY ACCEPTED ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES and to render an opinion on the fairness of the financial statements.

Auditor – Person who AUDITS financial accounts and records kept by others. Includes both public accounting firms registered with the PCAOB and associated persons thereof.

Auditors’ Report – Written communication issued by an independent CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANT (CPA) describing the character of his or her work and the degree of responsibility taken. An auditors’ report includes a statement that the AUDIT was conducted in accordance with GENERALLY ACCEPTED AUDITING STANDARDS (GAAS), which require that the AUDITOR plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the FINANCIAL STATEMENTS are free of material misstatement, as well as a statement that the auditor believes the audit provides a reasonable basis for his or her opinion. (See ACCOUNTANTS’ REPORT.)

Balance Sheet – Basic FINANCIAL STATEMENT, usually accompanied by appropriate DISCLOSURES that describe the basis of ACCOUNTING used in its preparation and presentation of a specified date the entity’s ASSETS, LIABILITIES and the EQUITY of its owners. Also known as a STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL CONDITION.

Board of Directors – Individuals responsible for overseeing the affairs of an entity, including the election of its officers. The board of a CORPORATION that issues stock is elected by stockholders.

Bookkeeping – The recording of all financial transactions undertaken by an individual or organization. A financial transaction is any event that involves money.

Capital Stock – Ownership shares of a CORPORATION authorized by its ARTICLES OF INCORPORATION. The money value assigned to a corporation’s issued shares. The BALANCE SHEET account with the aggregate amount of the PAR VALUE or STATED VALUE of all stock issued by a corporation.

Cash-Basis Accounting – A system of accounting in which transactions are recorded and revenues and expenses are recognized only when cash is received or paid.

Certified Public Accountant (CPA) – ACCOUNTANT who has satisfied the education, experience, and examination requirements of his or her jurisdiction necessary to be certified as a public accountant.

Chief Financial Officer (CFO) – The corporate executive who is responsible for overseeing the financial activities of an entire company. This includes signing checks, monitoring cash flow, and financial planning.

Controller – An employee, often an officer, of a business firm who checks expenditures, finances, etc.; comptroller.

Corporation – Form of doing business pursuant to a charter granted by a state or federal government. Corporations typically are characterized by the issuance of freely transferable CAPITAL STOCK, perpetual life, centralized management, and limitation of owners’ LIABILITY to the amount they invest in the business.

Credit – Entry on the right side of a DOUBLE-ENTRY BOOKKEEPING system that represents the reduction of an ASSET or expense or the addition to a LIABILITY or REVENUE. (See DEBIT.)

Creditor – Party that loans money or other ASSETS to another party.

Debtor – Party owing money or other ASSETS to a CREDITOR

Debit – Entry on the left side of a DOUBLE-ENTRY BOOKKEEPING system that represents the addition of an ASSET or expense or the reduction to a LIABILITY or REVENUE. (See CREDIT.)

Disclosure – Process of divulging accounting information so that the content of FINANCIAL STATEMENTS is understood.

Dividends – Distribution of earnings to owners of a CORPORATION in cash, other ASSETS of the corporation, or the corporation’s CAPITAL STOCK.

Double-Entry Bookkeeping – Method of recording financial transactions in which each transaction is entered in two or more accounts and involves two-way, self-balancing posting. Total DEBITS must equal total CREDITS.

Equity – Residual interest in the ASSETS of an entity that remains after deducting its LIABILITIES. Also, the amount of a business’ total assets less total liabilities. Also, the third section of a BALANCE SHEET, the other two being assets and liabilities.

Expenses – Costs incurred in the normal course of business to generate revenues.

External Auditors – Independent CPAs who are retained by organizations to perform audits of financial statements.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) – Independent, private, non-governmental authority for the establishment of ACCOUNTING principles in the United States.

Financial Statements – Presentation of financial data including BALANCE SHEETS, INCOME STATEMENTS and STATEMENTS OF CASH FLOW, or any supporting statement that is intended to communicate an entity’s financial position at a point in time and its results of operations for a period then ended.

First in, First out (FIFO) – ACCOUNTING method of valuing INVENTORY under which the costs of the first goods acquired are the first costs charged to expense. Commonly known as FIFO.

Fraud – Wilful misrepresentation by one person of a fact inflicting damage on another person.

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) – Conventions, rules, and procedures necessary to define accepted accounting practice at a particular time. The highest level of such principles are set by the FINANCIAL ACCOUNTING STANDARDS BOARD (FASB).

Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (GAAS) – Standards set by the American Institute Of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) which concern the AUDITOR’S professional qualities and judgement in the performance of his or her AUDIT and in the actual report.

Income Statement – Summary of the effect of REVENUES and expenses over a period of time.

Interest – Payment for the use or forbearance of money.

Internal Auditors – An independent group of experts in controls, accounting, and operations, who monitor operating results and financial records, evaluate internal controls, assist with increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of operations, and detect fraud within the company where employed.

Internal Revenue Code – Collection of tax rules of the federal government. Also referred to as Title 26 of the United States Code.

Inventory- Tangible property held for sale, or materials used in a production process to make a product.

Invoice – (or bill) a commercial document issued by a seller to the buyer, indicating the products, quantities, and agreed prices for products or services the seller has provided the buyer. An invoice indicates the buyer must pay the seller, according to the payment terms.

Journal – an accounting record in which transactions are first entered; provides a chronological record of all business activities.

Last in, First out (LIFO) – ACCOUNTING method of valuing inventory under which the costs of the last goods acquired are the first costs charged to expense. Commonly known as LIFO.

Ledger – Any book of ACCOUNTS containing the summaries of debit and credit entries.

Liability – DEBTS or obligations owed by one entity (DEBTOR) to another entity (CREDITOR) payable in money, goods, or services.

Liquidity – A company’s ability to meet current obligations with cash or other assets that can be quickly converted to cash.

No-Par Value – Stock or bond that does not have a specific value indicated. (See STATED VALUE.)

Par Value – Amount per share set in the ARTICLES OF INCORPORATION of a CORPORATION to be entered in the CAPITAL STOCKS account where it is left permanently and signifies a cushion of EQUITY capital for the protection of CREDITORS.

PCAOB – Public Corporation Accounting Oversight Board, a private-sector, non-profit corporation, created by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 to oversee the AUDITORS of public companies in order to protect the interests of investors and further the public interest in the preparation of informative, fair, and independent audit reports.

Qualified Opinion – AUDIT opinion that states, except for the effect of a matter to which a qualification relates, the FINANCIAL STATEMENTS are fairly presented in accordance with GENERALLY ACCEPTED ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES (GAAP). The AUDITOR is required to qualify when there is a scope limitation.

Revenues – Increases in a company’s resources from the sale of goods or services; and earnings from INTEREST, DIVIDEND, rents.

Revenue Recognition Principle – The concept that revenues should be recorded when (1) the earnings process has been substantially completed and (2) an exchange has taken place.

Stated Value – Per share amount set by the BOARD OF DIRECTORS to be placed in the CAPITAL STOCK account upon issuance of NO-PAR VALUE.

Statement of Cash Flows: The financial statement that shows an entity’s cash inflows (receipts) and outflows (payments) during a period of time.

Statement of Financial Condition – Basic FINANCIAL STATEMENT, usually accompanied by appropriate DISCLOSURES that describe the basis of ACCOUNTING used in its preparation and presentation as of a specified date, the entity’s ASSETS, LIABILITIES and the EQUITY of its owners. Also known as BALANCE SHEET.

Transactions – Exchange of goods or services between entities (whether individuals, businesses, or other organizations), as well as other events having an economic impact on a business.

Unqualified Opinion – AUDIT opinion not qualified for any material scope restrictions nor departures from GENERALLY ACCEPTED ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES (GAAP). The AUDITOR may issue an unqualified opinion only when there are no identified material weaknesses and when there have been no restrictions on the scope of the auditor’s work. Also known as “clean opinion”.

The statements or comments contained within this article are based on the author’s own knowledge and experience and do not necessarily represent those of the firm, other partners, our clients, or other business partners.

Meigs, Walter B. and Robert F. Meigs. Financial Accounting, 4th ed. McGraw-Hill, 1970, p.1

Accounting Terminology Guide, New York State Society of CPAs and Utah Association of Certified Public Accountants Accounting Glossary