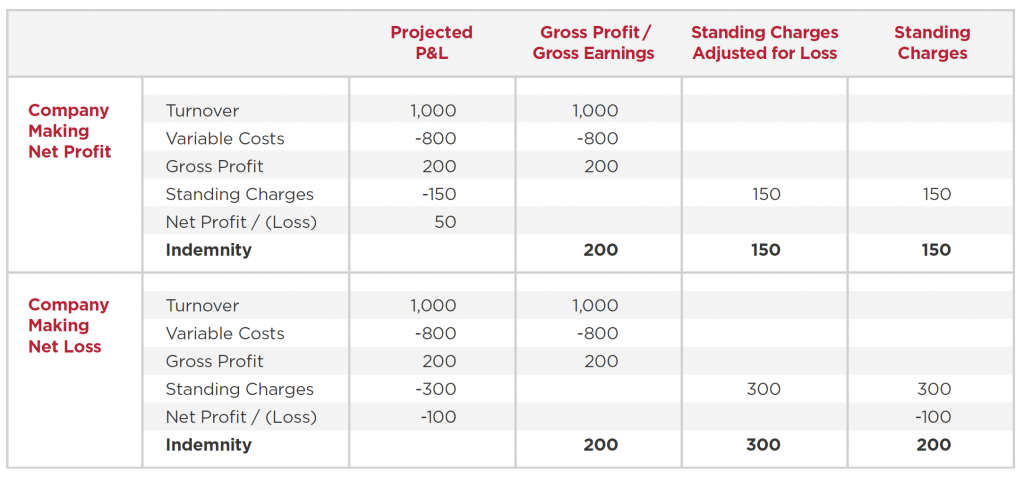

When it comes to Business Interruption policies for Oil & Gas risks, there are different types of coverage available in the market, including Gross Profit, Gross Earnings, Specified Standing Charges etc.

Common Policy Wordings

Gross Profit equates to Turnover less Uninsured Working Expenses (likely to be the variable expenses of the business) and should provide a proper indemnity that will put the insured back in the same financial position it would have been in, but for the damage, subject to the application of deductibles, policy limits / sub-limits and average clauses. By deducting Variable Costs from Turnover, Gross Profit essentially equates to insuring Standing Charges (i.e., Fixed Costs) plus Net Profit.

Gross Earnings equates to the sales value of lost production (let’s assume this is similar to Loss of Turnover) less any expenses that do not continue due to the loss. We will discuss how both wordings may address some of the issues noted below. Policies that insure Specified Standing Charges will not necessarily put the insured back in the same financial position, but for the damage, unless the expected net profit was zero. Standing Charges are usually the Fixed Costs incurred by the business and common examples include Labour Costs, Repair & Maintenance Costs, Overhead Costs, Depreciation as well as General & Administration Costs. Some policies require, in the definition of Standing Charges, an adjustment for a ‘net trading loss’, whereby an adjustment has to be made to bring the indemnity in line with the Gross Profit wording and avoid a ‘windfall’ gain to the insured.

The table below sets out the possible scenarios of indemnity in simple terms.

Types of Refining Margin

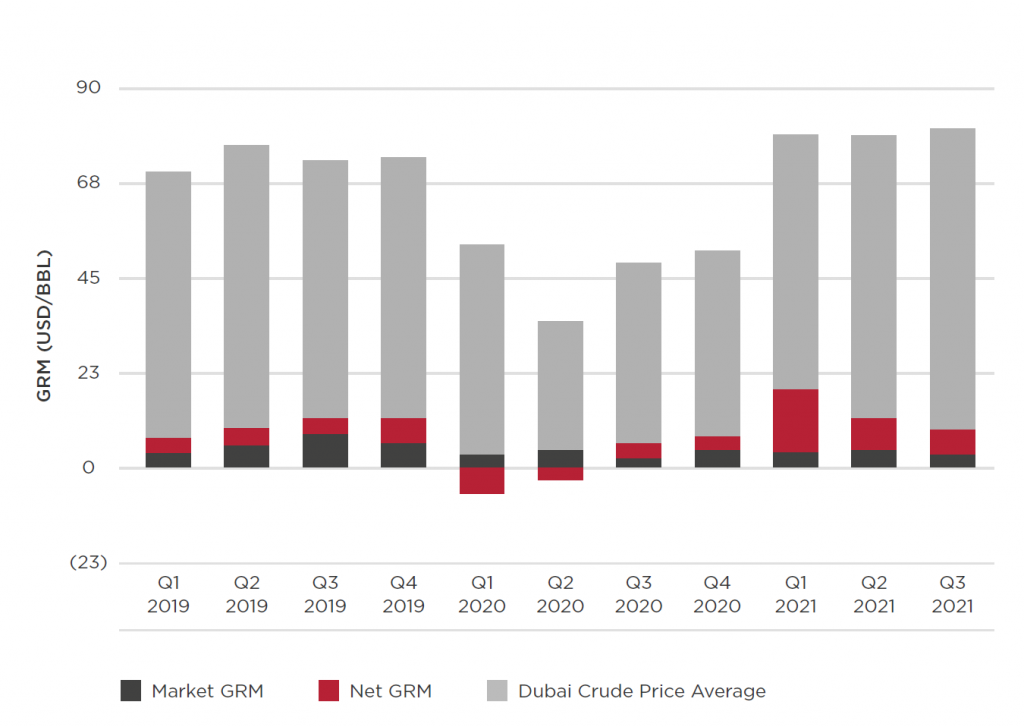

Gross Refining Margin (“GRM”) is a common term used in the oil & gas industry, which represents the difference in value between the refined products that are sold and the feedstocks (crude and other feeds) that are consumed, generally calculated per barrel of crude oil processed. GRM provides a good benchmark for investors in comparing the refiner’s performance across periods.

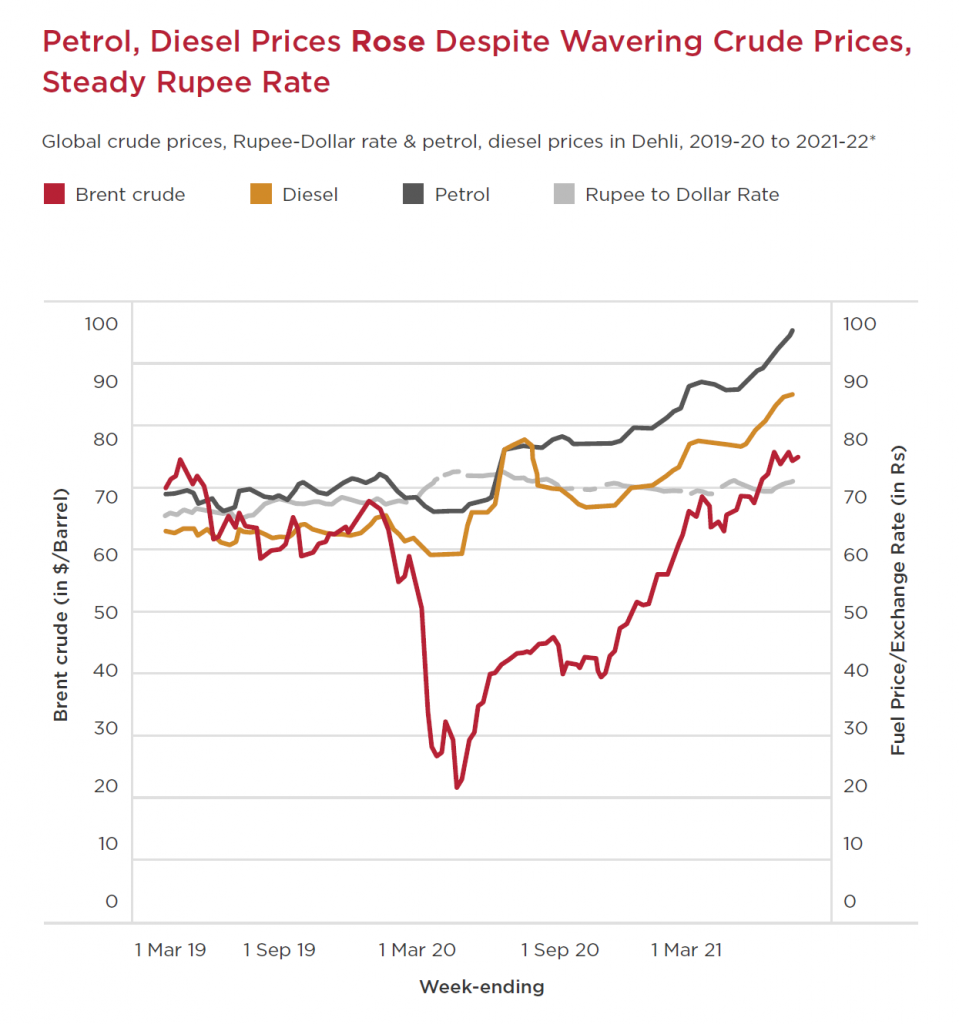

GRM can be very volatile, as changes in crude oil purchase prices may not be immediately reflected in refined product selling prices. In other words, change in refined product prices might be at a faster or slower pace than the change in crude oil prices.

The chart below illustrates the prices of crude oil, petrol and diesel in India over the past few years. Interestingly, petrol and diesel prices did not follow crude oil prices. In fact, they increased even during the significant decline in crude oil prices fuelled by the Covid-19 pandemic. Therefore, when evaluating refining losses, analysis of the GRM and the market impacts driving the GRM are critical.

Many refining companies will therefore report their refining margins on two bases: i) the GRM based on market prices for feedstocks and refined products; and ii) the GRM taking account of inventory movements.

The chart below shows the quarterly margins reported by a refinery in Thailand from 2019 to 2021.

What is the difference between Insurance Gross Profit and GRM? They are relatively similar, except that GRM does not usually consider other variable costs such as chemicals/catalysts, utilities and variable selling costs.

Evaluating a Business Interruption Claim

Irrespective, it is not appropriate to measure the loss based on the historic / indemnity period GRM or the accounting gross profit reported in the profit and loss statements as it is often impacted by changes in the value of crude oil inventory. During a period of upward oil price trend, the refining cost of crude from tank inventory is lower than current crude oil prices, thereby resulting in higher refining margin. On the other hand, refiners will experience lower (or possibly negative) refining margins, when the current crude prices are lower than the cost of crude stock used from inventory that was purchased at a higher value.

In order to evaluate the true economic impact of an interruption to a refinery or petrochemical plant, it is more accurate to calculate the Standard Turnover and Rate of Gross Profit based on the actual indemnity period prices (reported in monthly sales / purchase reports), rather than historic prices or actual inventory prices during the indemnity period, as this represents the sales value the Insured would have achieved and the feedstock cost it would have avoided (assuming purchases are curtailed at the time of the loss), but for the loss. How do the common BI wordings apply in this context?

Gross Profit Wording

A standard Gross Profit wording is accompanied by what is often referred to as the ‘trend clause’, ‘adjustment clause’ or ‘other circumstances clause’. This clause essentially provides flexibility to adjust historic figures, such that they reflect the results (i.e. the Turnover and Gross Profit) that would have been achieved, absent the loss.

Two debates often ensue when measuring a loss under Gross Profit wording.

Firstly, a debate can ensue about whether it is appropriate to adopt the inventory prices or the avoided purchase prices during the indemnity period.

If the indemnity period inventory prices are adopted, then there will inevitably be a period of months after the plant resumes production when the margins continue to be impacted by the damage, as the inventory prices that are rolled forward do not reflect the ‘but for the loss’ inventory prices that would have been rolled forward. In most cases, the two approaches will result in the same outcome (unless the interruption continues close to the end of the maximum indemnity period) and therefore the simplest approach to calculate the loss is to adopt the avoided purchase prices as this can be done immediately after the end of the interruption and is simpler to follow.

Secondly, the wording prescribes us to apply a projected Rate of Gross Profit (“ROGP”) to the reduction in Turnover, which is not the same as comparing the actual gross profit to the projected gross profit. In complex refinery and petrochemical claims, it is often the case that the ROGP achieved on actual turnover during an indemnity period is different (usually lower) compared to the projected ROGP. This is especially the case if a loss involves a unit like a cracker, which breaks down heavier hydrocarbons into lighter more valuable hydrocarbons and adds significantly to a plant’s margins. The Gross

Profit wording does not provide an obvious way to include the deterioration of the margin on the balance of production that continues, even if it clearly arises as a result of the loss. The Departmental Clause certainly assists, if the results of each unit could be segregated as a separate department, but this is often difficult in practice. The common ‘litmus test’ in such situations is to determine whether an insured has operated the plant in such a way that has mitigated insurers’ loss.

Gross Earnings Wording

Typical policy language covers reduction in gross earnings less charges and expenses which do not necessarily continue subject to ACTUAL LOSS SUSTAINED (emphasis added). The most common broad definition of gross earnings is total sales value of production less cost of raw stock (crude oil and possibly other purchased intermediates) and supplies consumed in the conversion process. Typically, crude costs and product slate pricing are based on values during the interruption period which can be contractual in nature. Disputes can arise when there are large swings in price shortly before or after an interruption period.

Approach to Calculating Loss of Gross Profit or Gross Earnings

In respect of Projected Gross Profit, this represents the difference between Standard Turnover and Projected Variable Costs (primarily crude).

In respect of Standard Turnover, we typically calculate it based on the projected product slate, valued at actual indemnity period prices. The refinery will continually optimise the crude and product slates to maximize profitability. Hence, it is important to evaluate and select the representative period used as the bases to project the product slate.

Similar to Standard Turnover, we also value the projected crude slate at actual indemnity period purchase prices to arrive at projected crude costs. Crude slates represent the blend of crude oil processed by a refinery and refiners usually use crude from several sources in order to produce the most desirable and valuable refined products (i.e. the product slate).

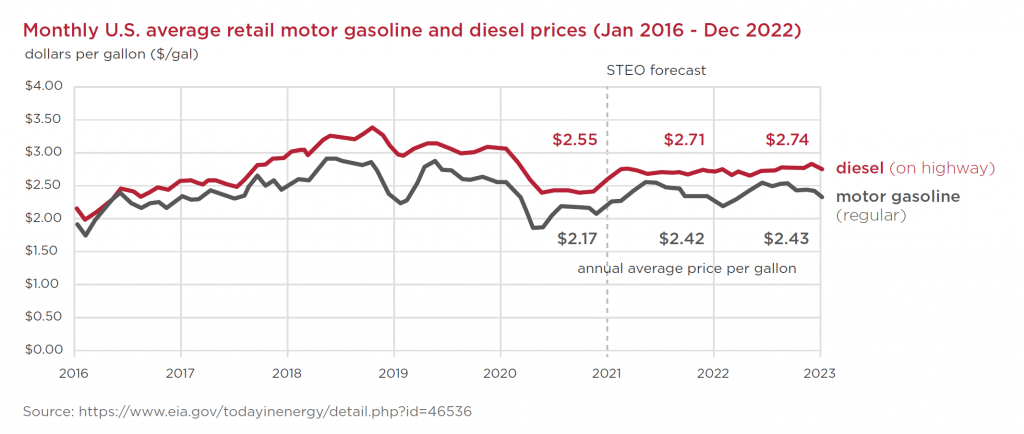

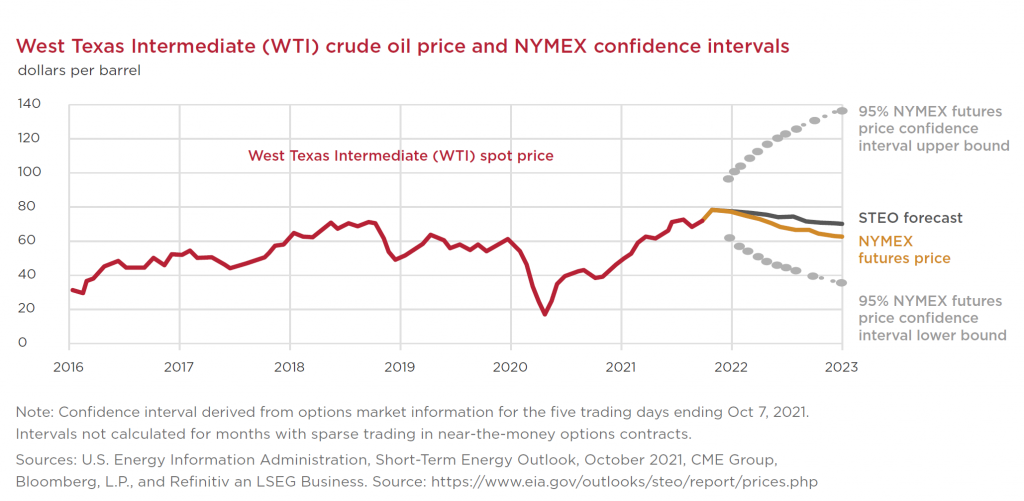

Why are actual indemnity period prices adopted? The images below illustrate the movement in prices of diesel, gasoline and West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil over the past years, which could be influenced by various factors such as supply and demand impact, political instability, global economy, and pandemic.

The most recent decline of prices in 2020 (especially during the first half of 2020) was associated with the Covid-19 pandemic. The impact of travel restrictions and reduced economic activity resulted in a surplus in supply and a significant drop in demand. We observe a rebound in prices with a further relaxation of the measures and an improving economic climate. As such, if we were to measure the loss sustained in 2020, it would not be appropriate to adopt pre-pandemic prices as it would not represent the prices which would have been incurred by the Insured.

Our earlier technical briefing on the use of Linear Program (“LP”) Models to assess the standard turnover and gross profit highlighted that the LP model should factor in the total value of the feedstocks input to the process and the total value of the saleable production from the refinery. Most refineries us e fu els generated in the refining process to generate their own utility requirements and some create a surplus of steam and electricity that is sold to third parties. However, the LP model may not consider other variable costs incurred such as utilities purchased from third parties, chemical and catalyst costs, freight and other variable selling expenses or duties / other government levies.

Therefore, it is important to identify all of the variable costs in the profit and loss statements and ensure that the variable costs are accounted for, either in the LP model assessment or in a separate adjustment to the loss.

The statements or comments contained within this article are based on the author’s own knowledge and experience and do not necessarily represent those of the firm, other partners, our clients, or other business partners.