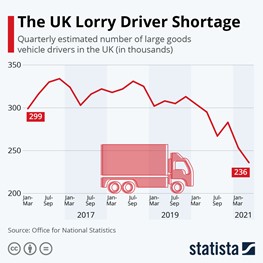

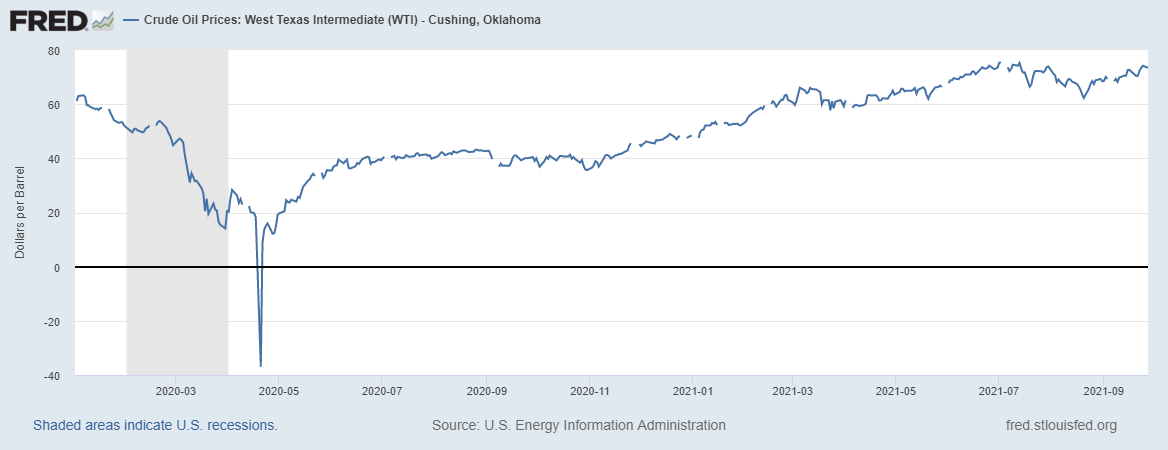

Covid-19 has led to major disruptions across various sectors and the petroleum industry is no exception. Demand for oil and petroleum products, in general, declined due to reduced economic activity as governments worldwide imposed lockdowns and tightened border controls. Certain sectors, such as aviation and transportation, were particularly affected and prices of gasoline, diesel and jet fuel tumbled as a result. Naturally, this had an impact on upstream processes as well. Refineries began to alter their output mix, run at reduced rates or even shut down entirely in the face of adverse market conditions, while US crude prices briefly veered into negative territory over concerns about excess supply and insufficient storage capacity (see Chart 1 below). Overall, world oil demand declined by 9.6 million barrels per day from 2019 to 2020 according to OPEC estimates (see Chart 2 below).

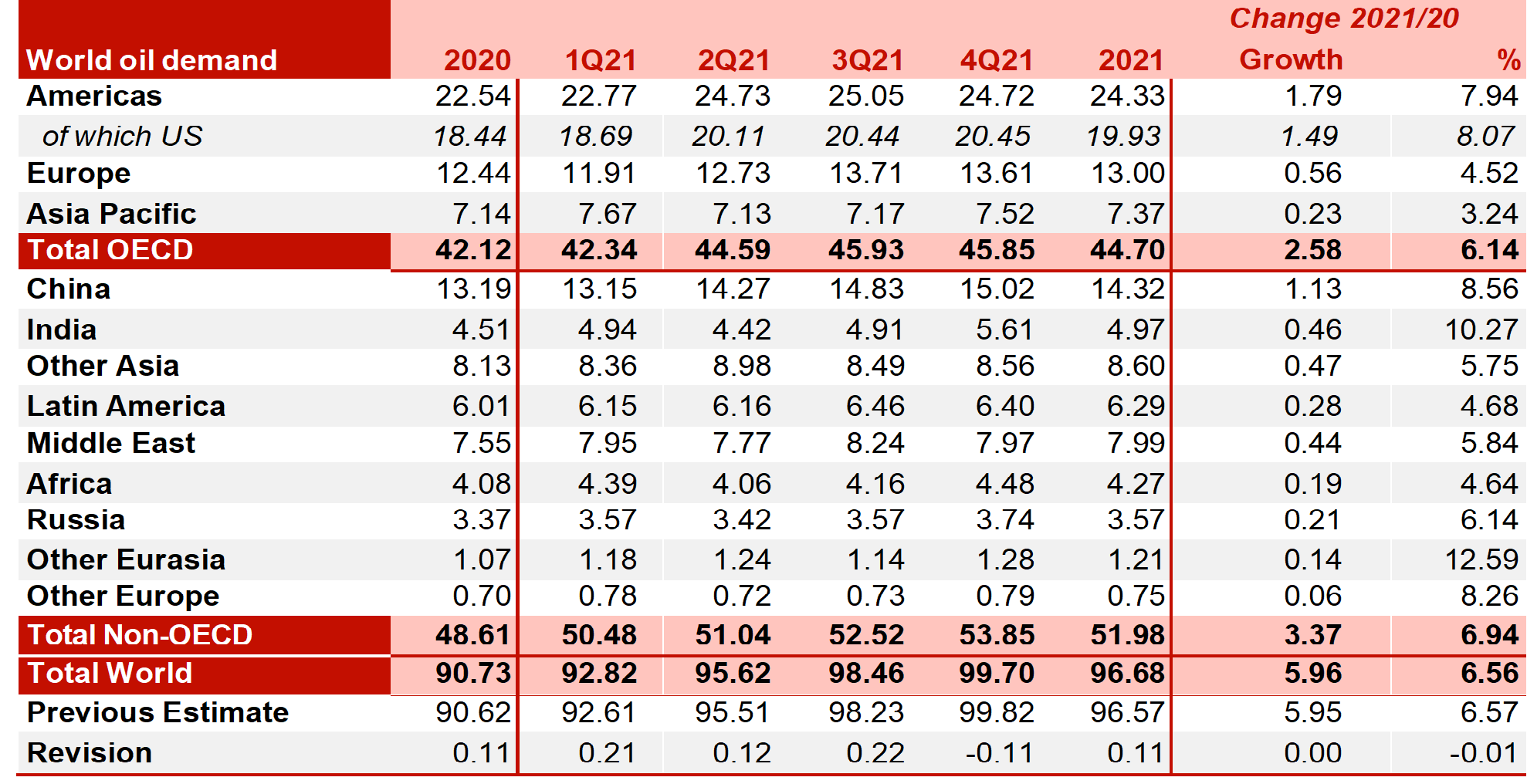

As the world adapted to living with the pandemic, supported in part by substantial stimulus packages, economic activity has begun to recover. This optimism has been further bolstered by successful vaccine rollouts and subsequent lifting of pandemic restrictions across a number of countries. Although there has been increasing attention on green energy and sustainability in recent years, fuels derived from crude oil remain crucial to meeting energy needs and various industries continue to utilise petrochemicals within their processes. As such, demand for oil and petroleum products has picked up (see Table 1 below) and, in a number of instances, prices have exceeded pre-pandemic levels. Nonetheless, as the past two years have shown, it is impossible to predict the future with a high degree of certainty and the trajectory of the recovery remains to be seen.

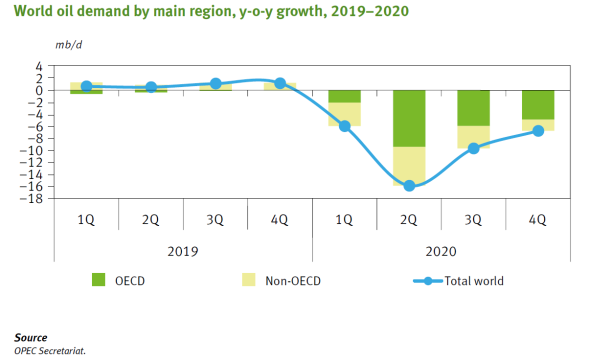

In spite of this recovery, motorists across the UK have struggled to fill up their vehicles in the past week as forecourts dried up and were unable to be replenished in time. Industry and government spokesmen have emphasised that there is no shortage of petrol and diesel as ample supplies are available at refineries. The root cause of this crisis has been identified as a shortage of heavy-goods vehicle (HGV) drivers (see Chart 3 below), brought about by a perfect storm of various factors, including Brexit, the pandemic as well as inadequate pay and working conditions. In recent days, alleviating measures such as deploying Army resources, relaxation of competition laws and a short-term visa scheme for foreign HGV drivers have been announced, although experts warn this is a long-term structural issue. This recent turn of events serves as a reminder that where complex supply chains exist, general industry trends may not necessarily apply and the recovery from a period of depressed activity might take longer than expected.

From an insurance perspective, price volatility can certainly lead to volatility in refining and petrochemical margins. However, higher oil and gas prices do not automatically mean higher business interruption claims – this topic will be explored in-depth in one of our future Oil & Gas technical briefings in the coming months.

By Yiyan Lin and Phillip Taylor.

The statements or comments contained within this article are based on the author’s own knowledge and experience and do not necessarily represent those of the firm, other partners, our clients, or other business partners.

Chart 1: WTI Crude Oil Prices

Chart 2: Global Oil Consumption Growth – Year 2019 to Year 2020

Table 1: World Oil Demand in 2020 and 2021

Chart 3: Number of HGV Drivers in UK, by Quarter